Michelangelo Merisi, also Michael Angelo Merigi, called Caravaggio [karaˈvadd͡ʒo] for short after his parents' place of origin (Caravaggio in Lombardy) (b. September 29, 1571 in Milan; † July 18, 1610 in Porto Ercole on Monte Argentario), was an important Italian painter of the early Baroque.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, together with Annibale Carracci, is considered the overcomer of Mannerism and the founder of Roman Baroque painting. While Carracci ushered in Baroque classicism, Caravaggio's style is characterized by a novel and naturalistic pictorial design, which he executed with a refined and stylcontrastinge of chiaroscuro, chiaroscuro painting.

In his treatment of Christian themes he broke new ground by linking the sacred with the profane. With his new style, Caravaggio exerted a lasting influence on many Italian, Dutch, French, German, and Spanish painters of the early Baroque period, who are often referred to as Caravaggists (including the Utrecht Caravaggists).

Caravaggio led an eventful life. After an apprenticeship with Simone Peterzano in Milan, he traveled to Rome, where he rose from penniless artist to the favored painter of the Roman cardinals. He was banished from Rome for manslaughter and settled in Naples and later Malta.

In Malta he was made a Knight of the Order of Malta, but fled from there to Sicily after a physical altercation and returned to Naples after a year. Waiting for his banishment from Rome to be lifted, he died at the age of 38 in Porto d' Ercole on Monte Argentario near Grosseto.

Soon after his untimely death, legends began to form that made him the "archetype of the wicked artist." The "Caravaggio myth" lives on to this day.\

Caravaggio's Life

Sources and legends on personality and character

The sources on Michelangelo Merisi's life are extensive, but not yet fully researched. What is known about him and his character comes on the one hand from police and trial records, and on the other hand mainly from some early biographies of contemporaries who knew him personally.

His first biographer was the Sienese physician and art lover Giulio Mancini, who was a friend of Caravaggio's first patron, Cardinal Francesco Maria Bourbon Del Monte (1549-1627), and who had treated Caravaggio in his household. His notes, completed in 1619, were never published during his lifetime, but they circulated in transcripts and were known to other biographers and writers on art.

Portrait of Cardinal Francesco Maria Bourbon Del Monte, Caravaggio's first patron, by Ottavio Leoni

Among them was Giovanni Baglione, who in 1642 published a biography of Caravaggio in his "source work on the artists active in Rome during his lifetime," Vite de'pittori, et scvltori et architetti.

From these sources, as from the numerous legal conflicts in which Caravaggio was involved for years, it is clear that he tended to behave aggressively and explosively, although it was still relatively harmless, for example, when he simply threw a plate of artichokes in the face of an "insubordinately responding waiter" in 1604.

Even Mancini, apparently an admirer of the painter, describes that the latter's "great skill in art was accompanied by an extravagance of manners," and "it cannot be denied that he was extremely self-willed, and that he took ten years off his life with these extravagances, and that the fame he had acquired by his profession was partly diminished."

Baglione, "an avowed enemy and rival of Caravaggio," published a biography of about three pages in his artist's vitae of 1642, 32 years after Caravaggio's death and nearly 40 years after a libel suit he had brought against Caravaggio and some of his friends, in which, in Ebert-Schifferer's opinion, he used "distortions of fact" and "subtle ... defamations" portrayed his erstwhile opponent as an "unpredictable" character.

This detail from Matthew's martyrdom is interpreted as a self-portrait of the master (around 1600)

Andrew Graham-Dixon, while emphasizing his accurate presentation of the facts, detects a certain "schadenfreude" in his morally smug conclusions. In his "begrudging assessment" (Roberto Longhi), Baglione writes:

"Michelangolo was a mocking and haughty man; and it sometimes happened that he spoke ill of all painters past and present, no matter how great they were; for it seemed to him that with his works alone he had surpassed all others in his profession. Michelangolo Amerigi,

due to excessive boldness of spirit, was a little dissolute [un poco discolo] and sometimes sought opportunities to break his neck or endanger the lives of others. Often in his company were men who were also by nature ruffians." (A brief account of the quarrel with Ranuccio Tomassoni that led to manslaughter follows).

The biography of Caravaggio contained in Giovan Pietro Bellori's artist vitae (Le vite de' pittori, scultori e architetti moderni), printed in 1672, is also a tendentious text that, while saying much about his work and patrons,

measures Caravaggio against an idealizing doctrine of art that harkens back to antiquity and Raphael. At the time, Roman classicism was at its peak; in the words of Boris von Brauchitsch, Caravaggio was therefore "stylized as the antipode of the beautiful, pure, divine Raphael."

More recent authors and Caravaggio experts evaluate the early biographies as unreliable sources, among them art historians Roberto Longhi of Italy, Andrew Graham-Dixon of Great Britain, and Sybille Ebert-Schifferer of Germany.

According to Roberto Longhi, "from the middle of the seventeenth century - from Bellori to Passeri - Caravaggio's unhappy fate is dressed up with a mixture of truth and falsehood, preparing the way for the fictionalized narratives in Romanticism."

The German author calls the picture these sources create of Caravaggio a "black legend," which she seeks to demystify on the basis of documents unearthed by intensive archival research. It is undoubted,

however, that Caravaggio was involved in discords, violent disputes, and court cases, and was also imprisoned several times in Rome and in Malta for insults, unauthorized possession of weapons, and serious physical attacks. Nevertheless, Ebert-Schifferer believes that his lifestyle was not unusual for the times in Italy.

Especially in circles of the nobility and among members of the middle class striving for social advancement, such assaults were socially completely normal. When Caravaggio,

for example, "beat(ed) an artist in the dark with the cry 'traitor' and gave him a sword thrust" in November 1600, this was, according to Ebert-Schifferer, "part of the ritual of settling scores from honor violations." Similarly, Graham-Dixon finds, "He was a violent man, but it is important to remember that he lived in a violent world."

Giorgio Bonsanti, an Italian art expert on the 14th to 16th centuries, notes that it has appealed to earlier writers to draw equations between the painter's character and his work; for example, his penchant for the "gloomy," which became apparent from about 1600, was interpreted as a reflection of the painter's "dark depths of the soul."

Bonsanti writes that this may be laughed at today, but he cannot help but state that "the basic extremist attitude, in itself estimable, which made him an unbending opponent of all conventions in art, turned in life into a lack of self-control, which manifested itself in blind fits of rage."

Caravaggio's sexual orientation, too, has been and continues to be a subject of rumor and conjecture. Partly from his subjects, partly from his lifestyle, conclusions have been drawn about his homosexuality and what is now called a pederastic inclination toward young boys.

In the 1603 libel trial brought against Caravaggio by Giovanni Baglione, one of the witnesses, the painter Tommaso Salini, mentioned almost in passing a "lust boy" of Caravaggio's. Some authors believe that these and similar statements would not stand up to scrutiny as sources. Ebert-Sc

hifferer, for example, is convinced that under source-critical aspects and with a historically informed view, no valid statements could be made about whether the sensual presence in his art was now "an expression of a homosexual personality" or owed to a "serene matter-of-factness" in his time.

In their biographies of Caravaggio, the Anglo-Saxon art historians Creight E. Gilbert and Helen Langdon similarly reject unequivocal statements regarding his sexual orientation. Graham-Dixon suspects a bisexual inclination in his practiced sexual life.

Origin, Youth, and Teaching: Milan (1571-1592)

His youth is the least documented period of Caravaggio's life. He was the son of Fermo Merisi, a self-employed master mason from Caravaggio, a town near Bergamo, and his second wife Lucia Aratori, whose family owned small estates.

Caravaggio was named after the archangel Michael, whose feast of the name coincided with the date of his birth. Michelangelo initially grew up in Milan. Because of a plague epidemic in 1576, the family returned to Caravaggio. The father and an uncle probably succumbed to this disease. At the age of ten he became an orphan.

In 1584, the thirteen-year-old Michelangelo entered a four-year apprenticeship with the well-known painter Simone Peterzano in Milan. Peterzano, by his own account a pupil of Titian, worked for the high Milanese aristocracy. Giorgio Bonsanti characterizes him as a "mediocre Milanese late mannerist."

The not inconsiderable apprenticeship fee was paid by the family. According to Ebert-Schifferer, Caravaggio spent the first 21 years of his life in a "largely fatherless but sheltered childhood and youth in a well-connected solidarity-based middle-class family circle in a small town."

Rise to painter of the cardinals: Rome (1592-1606)

Whether Caravaggio stopped in Venice on his journey to Rome is debatable, but not that he was familiar with Venetian painting, if only through his teacher Peterzano, who maintained intensive relations there.

It is more likely that he stopped in Bologna, where the two brothers Agostino and Annibale Carracci, as well as their cousin Ludovico Carracci, had first achieved fame for their revolutionary style of painting.

Boy with fruit basket (1593/94), Galleria Borghese, Rome

In 1592 at the latest, he settled penniless in Rome. There he initially found lodgings with a prelate, Pandolfo Pucci, but according to his early biographers, he soon left again because of the modest and down-to-earth (frugal) meals.

Probably during an extended hospital stay, he created the painting, modernly titled Little Sick Bacchus (Bacchino malato 1593, Galleria Borghese, Rome), of a young man in greenish complexion. This youth, loosely draped with a shirt-like cloth, with ivy in his dark curls and grapes in his right hand, is, according to experts, a mythologically disguised self-portrait.

Small sick Bacchus (1593), Galleria Borghese, Rome

He became an employee in various painting workshops, including the studio of Giuseppe Cesari, the artist favored by Pope Clement VIII. Initially responsible for flowers and fruits, he was able to learn "how to market his art and behave in an upward manner" in the workshop of his famous colleague, who was only three years his senior.

It was probably there that he met Prospero Orsi, a colleague specializing in painting grotesques, "who was to become Caravaggio's most important advocate and his agent in the art market."

In one of the workshops he became friends with Mario Minniti, a Sicilian six years his junior who was also a painter. Their friendship lasted even beyond the spatial separation until Caravaggio's death. He was also friends with the lawyer, poet, and architect Onorio Longhi, a "doctor of both rights" and "police-known rioter."

After a few years Caravaggio went into business for himself and joined the Brotherhood of Painters. He was probably helped by Prospero Orsi. Not only did he provide him with lodgings in the palace of Monsignor Fantino Petrignani,

which the latter had left to his nephew during an extended absence from Rome; he also induced his brother-in-law Gerolamo Vittrici, the deputy papal chamberlain, to buy three paintings by Caravaggio.

These paintings were The Gypsy Reading Her Hand (1594, Louvre, Paris), The Penitent Magdalene, and Rest on the Flight into Egypt (both 1594, Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome). This period also saw Caravaggio's turn to sacred subjects.

After Caravaggio came to the attention of the art-loving and influential Cardinal Francesco Maria Bourbon Del Monte, he took him in as a member of the household (the famiglia) in his Palazzo Madama, probably in late 1595. "Thus he gained board, lodging and, above all, high protection, but was also allowed to work for other patrons with the patron's consent."

The Musicians (1595), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The "bohemian existence" he had led until then thus came to an end. For about five years he lived in Del Monte's palace. After that he found accommodation in Palazzo Mattei, the household of Cardinal Girolamo Mattei and his brothers Ciriaco and Asdrubale.

The number of aristocrats and church dignitaries who commissioned paintings from him grew by leaps and bounds. Among them was Cardinal Scipione Borghese, the nepot of Pope Paul V and founder of the Villa Borghese with the Galleria Borghese collection of paintings.

Six of the 18 members of the Apostolic Chamber alone were among Caravaggio's patrons. Del Monte, a music lover and advocate of church music reform, commissioned him for paintings such as The Musicians (1595,

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), in which Caravaggio is said to have depicted himself as one of the four musicians, and The Lute Player, of which two versions exist (1595/96, Hermitage, St. Petersburg - replica 1596, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

Medusa (etwa 1597), Uffizi Gallery, Florenz

The first version, with a masterful still life of flowers and fruit, had been ordered by Del Monte's neighbor, the banker Vincenzo Giustiniani, from whom Del Monte then received a replica in Caravaggio's hand.

He mastered the commission for the mythological theme of Medusa (1597/98, Uffizi, Florence) as a "virtuoso piece" on a "shield-shaped piece of poplar wood covered on canvas," a tournament shield, which, however, had never been used as such. Cardinal Del Monte, who had commissioned the painting, gave it as a gift to the Medici collection.

Del Monte's estate also included the painting of St. Catherine (1597/1598, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid), whom the cardinal particularly admired. Caravaggio depicted the martyr in splendid garb and unspoiled beauty.

Caravaggio received a number of prestigious commissions for religious works depicting violent battles, grotesque beheadings, torture, and death. The most notable and technically masterful of these were The Infidel Thomas (c. 1601) and The Capture of Christ (c. 1602) for the Mattei family, rediscovered only in the 1990s in Trieste and in Dublin after remaining unrecognized for two centuries.

The Last Supper at Emmaus (1601), National Gallery, London

By and large, each new painting increased his fame, but some were rejected by the various patrons, at least in their original form, and had to be repainted or find new buyers. The problem was essentially that while Caravaggio's dramatic intensity was appreciated, his realism was seen by some as unacceptably vulgar.

His first version of Matthew and the Angel, showing the saint as a bald peasant with dirty legs accompanied by a lightly clad boy angel, was rejected, so a second version had to be painted as The Inspiration of Saint Matthew.

The Conversion of St. Paul was also rejected, and another version of the same subject, The Conversion on the Road to Damascus, was accepted but showed the horse's haunches of the saint far more prominently than the saint himself,

leading to a discussion between the artist and an angry official of Santa Maria del Popolo: "Why did you put a horse in the middle and St. Paul on the ground?" he asked. "Is the horse God?" "No, but it is in God's light!"

Aristocratic collector Ciriaco Mattei, brother of Cardinal Girolamo Mattei, a friend of Cardinal Francesco Maria Bourbon Del Monte, gave for the city palace he shared with his brother, The Last Supper in Emmaus (1601, National Gallery, London), 1601 (National Gallery, London),

Doubting Thomas, 1601 "Ecclesiastical Version" (Private Collection, Florence), The Infidel Thomas, 1601 "Secular Version" (Sanssouci Palace, Potsdam), John the Baptist with the Ram (1602, Capitoline Museums, Rome), and The Capture of Christ (1602, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin).

The second version of the Captivity of Christ, looted from the Odessa Museum in 2008 and recovered in 2010, is believed by some experts to be a contemporary copy.

Doubting Thomas is one of the most famous paintings by the Italian Baroque master Caravaggio, circa 1601-1602.

The Unbelieving Thomas (Ecclesiastical Version, 1601), Private Collection, Florence, Italy

There are two autograph versions of Caravaggio's Doubting Thomas, an ecclesiastical "Trieste" version for Girolamo Mattei now in a private collection and a secular "Potsdam" version for Vincenzo Giustiniani (Pietro Bellori) and later entered the Prussian Royal Collection and survived World War II unscathed and can be admired in the Palais in Sanssouci, Potsdam.

It depicts the episode that led to the term "Doubting Thomas," officially known as "Doubting Thomas," which has been frequently depicted and used to make various theological statements in Christian art since at least the 5th century. According to John's Gospel,

the apostle Thomas missed one of Jesus' appearances to the apostles after his resurrection, saying, "Unless I see the marks of the nails in his hands, and put my finger where the nails were, and put my hand into his side, I will not believe." A week later Jesus appeared and told Thomas to touch him and stop doubting. Then Jesus said, "Because you have seen me, you have believed; blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed."

The two images show in a demonstrative gesture how the doubting apostle puts his finger in the side wound of Christ, the latter guiding his hand. The unbeliever is depicted like a peasant, dressed in a robe torn at the shoulder and with dirt under his fingernails. The composition of the picture is such that the viewer is directly involved in the event and feels the intensity of the process.

It should also be noted that in the ecclesiastical version of the unbelieving Thomas, the thigh of Christ is covered, while in the secular version of the painting, the thigh of Christ is visible.

The commissions for two funeral chapels (Cappella Contarelli in the church of San Luigi dei Francesi and Cappella Cerasi in the church of Santa Maria del Popolo) [see below: "Commissions for Roman Churches"] made his style known to a wider audience. The resulting notoriety brought him new orders and contacts with the wealthy, and established his status as one of the city's leading painters.

Caravaggio's involvement in an altercation that ended in violence and manslaughter on May 29, 1606, caused him to flee Rome. He had gotten into a quarrel with Onorio Longhi during a street party on the anniversary of Paul V's election as pope on May 28, 1606,

The Seven Works of Mercy (1606/07), Naples, Pio Monte della Misericordia

during which he ended up injuring Ranuccio Tomassoni, son of the commander of Castel Sant'Angelo, which served as a state prison, so severely with a sword thrust that he died shortly thereafter. Caravaggio was initially only a minor figure in relation to the cause of the quarrel, because he only wanted to assist his friend Longhi in the dispute between Longhi and the Tomassoni.

The dispute with fatal outcome was based on an older quarrel, about the causes of which, however, the sources make divergent statements. All those involved in the violent quarrel were sought by arrest warrant, sentenced and exiled. Since neither investigation files nor verdicts have been preserved, the exact punishments are unknown.

According to Graham Dixon, Caravaggio met the most severe punishment: in public notice (Avvisi of May 31, 1606), he was banished indefinitely from Rome and, as a convicted murderer, was given the "bando capitale," which meant that anyone from the papal states could kill him with impunity.

Favorite of the Neapolitan nobility: Naples (1606-1607)

Caravaggio had been seriously injured in the sword fight itself. After his wounds had been treated, he packed up the most necessary utensils in his lodgings and went with his young assistant Cecco to the neighboring palace of the Colonna family, who sponsored him.

The next morning he fled in their carriage to the principality of Paliano, south of Rome, which was ruled by the Colonna family. He initially found refuge there on the feudal estates of Don Marzio Colonna.

The Flagellation of Christ (1607)

In the fall of 1606, he moved on to the Spanish kingdom of Naples, where the exile from Rome became "within a few months, he most famous and prolific artist in Naples." The Neapolitan nobility commissioned him to paint the altarpiece Seven Works of Mercy (1606/07) for the Pio Monte della Misericordia, Naples' leading charitable association.

He received other well-rewarded commissions from wealthy upstarts and from the viceroy himself. The wealthy and later ennobled Tommaso de Franchis acquired from him the Flagellation of Christ (1607, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples). According to Graham-Dixon, the two paintings received "stunned admiration" and changed Neapolitan painting overnight.

Knights of the Order of Malta: Malta and Sicily (1607-1608)

After about ten months of stay, Caravaggio left Naples. He boarded a galley belonging to his patron family Colonna on June 25, 1607, which took him to Malta, where he was received as a celebrated artist and became a Knight of the Order of Malta on July 14, 1608.

The Order was subject to the Vatican, while the island was a Spanish fiefdom. Caravaggio had probably prepared the friendly reception with gifts of paintings to high-ranking personalities. Nevertheless, his admission to the order required an exceptional permission of the pope.

In Malta, Caravaggio produced at least five works, including two portraits of the Grand Master of the Order, a Sleeping Cupid (1608, Palazzo Pitti, Florence) and St. Jerome (1607/08, St. John Museum, La Valletta).

The Beheading of John the Baptist (1608), oil on canvas, 361 × 520 cm

His major work during his stay in Malta was the monumental painting The Beheading of John the Baptist (1608, Oratory of the Basilica San Giovanni, Valletta), his largest format work.

When the painting was unveiled, Caravaggio was in prison for having participated in a riot involving the injury of a knight. Without waiting for the conclusion of the trial, he fled from prison on October 6, 1608. For leaving the island in violation of the statutes, he was expelled from the Order on December 1, 1608.

Caravaggio fled to Sicily, where his friend from earlier years, Mario Minniti, lived. Here he stayed for about a year in various cities, including Syracuse and Messina.

In Syracuse he left behind the altarpiece Burial of St. Lucia (1608, Santa Lucia al Sepolcro, Syracuse) and in Messina The Raising of Lazarus (1609, Museo Regionale di Messina).

Last Years: Waiting for Pardon and Early Death (1608-1610)

After barely a year, he left Sicily and initially settled back in Naples, where he once again worked for high-ranking clients. For Prince Marcantonio Doria he painted The Martyrdom of St. Ursula (1610, Palazzo Zevallos, collection of the Banca Intesa, Naples). From a robbery in Naples he sustained a severe facial injury.

The Martyrdom of St. Ursula from 1610 is one of the last works by Caravaggio

On his way from Naples to Rome, he reached Porto Ercole, which belonged to the Spanish Stato dei Presidi, where he was going to receive his pardon. Before it reached him, he died on July 18, 1610, at the age of 38, in a hospital of Porto Ercole and was buried there in a cemetery.

Since 1956 his remains have been in the parish church of Sant'Erasmo. The exact cause of death is unknown. Andrew Graham-Dixon considers a heart attack to be possible. Boris von Brauchitsch suspects malaria as the cause of death, while Michel Drancourt and others suspect sepsis caused by the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus.

Caravaggio's Work

Working method and design features

Caravaggio painted almost exclusively panel and canvas paintings in oil technique, with a strikingly limited range of colors: He used primarily earthy tones such as brown, ocher, black, gray, and olive, enlivened here and there with white and red (rarely yellow); blues and greens hardly ever appear, especially after the early work, and when they do, they are usually in attenuated, broken form.

His pictorial compositions mostly take place indoors or in an indeterminable darkness with oblique incidence of light, while his contemporaries Annibale Carracci, Reni, or Domenichino, for example, painted many of their scenes in nature, or with views of nature, and also numerous frescoes.

Basically, Caravaggio's style became darker and darker, this is especially noticeable from about 1600, where he usually has the figures act in front of a completely black background.

Caravaggio did not believe in the traditional hierarchy of art genres with the historical picture as the highest. He considered still life and genre painting to be equivalent art genres.

If Caravaggio's forced statement in the trial of 1603 can be taken seriously, he counted Giuseppe Cesari ("Gioseffe"), Federico Zuccari, Pomarancio (Cristoforo Roncalli), Annibale Carracci and the landscape painter Antonio Tempesta among the colleagues or competitors he himself respected.

Vocation of St. Matthew (1600), oil on canvas, 322 × 340 cm, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome

All of the aforementioned painters belonged to the clearly established painters of Rome, who worked in a completely different style from his own.

In Valeska von Rosen's judgment, "nothing in Caravaggio's works, corresponded to what his contemporaries were used to seeing." Caravaggio designed scenes through chiaroscuro, painting in light and dark, to which he gave "a new and powerful effect."

He worked with a dramatizing use of obliquely incident, scatter-free highlighting and created spatiality with the gestures and movements emphasized by light effects, in which the figures were placed with an unusual resemblance to life (cf. accompanying illustration).

At the same time, the figures are clearly, sharply and plastically worked out - Caravaggio thus did not use a soft sfumato blurring the contours, as is known especially from Leonardo, Giorgione, Titian or Barocci; instead, the overall effect in Caravaggio's work is rather somewhat hard.

The contrast of the sceneries illuminated by the lateral incidence of light to the background, which is often kept very gloomy, also intensifies the foregrounding of the actual representation. His "consistently pursued emptying of the pictorial space as well as his extensive renunciation of details serve to leave all constructive possibilities to the light."

The "polarizing light direction, takes the place of the architecture that defined the structures in the Renaissance." His innovative style helped him to fame. Envy and imitation among fellow painters (see below: Caravaggism).

Caravaggio's way of depicting Christian themes, with his limited earthy and somber coloring, with extremely real and often poor-looking figures, with angels looking almost like ragamuffins,

with infants of Jesus and boys of St. John shamelessly presenting their naked genital region, or similar details-apparently without regard or interest for religious feelings, dignity, and ideals of beauty (the so-called decorum of the art theory of the time)-was decidedly unconventional. Among his contemporaries,

therefore, he by no means always met with undivided understanding or even approval. Thus, not only were harmless but "profane" details, such as the dirty feet of the pilgrim couple, criticized in his Madonna di Loreto (or Madonna of the Pilgrims, Sant'Agostino, Rome),

St. John the Baptist with the ram, 1602, 129 × 95 cm, Capitoline Museums, Rome

several other of his church paintings were rejected in their first version by church patrons and had to be repainted by him; others were rejected outright, such as the Madonna dei Palafrenieri, also known as the Madonna with the Serpent, originally intended for a chapel in St. Peter's Basilica (today: Galleria Borghese, Rome), and the Death of Mary for Santa Maria della Scala (today: Louvre, Paris).

Nevertheless, the corresponding paintings found buyers in some art-savvy contemporaries who admired the painterly brilliance and appreciated in his paintings just this integration of the saint in the profane, that is, the connection of "sacred event and everyday experience", his endeavor to "integrate pious devotion into the sphere of the sensual", to [impose] the "lower, creaturely aspects on the highest objects of biblical history".

While Carracci strove for the Raphaelian ideal of beauty, Caravaggio sought to depict unidealized reality; to this end, he often chose the moment of supreme drama. Contrary to Renaissance painting, which directed the viewer's gaze into the depths of space, Caravaggio preferred to expand the pictorial space forward, drawing the viewer into the picture.

In many of his paintings, Caravaggio adopted gestures and details from the works of his great predecessors and competitors, foremost among them ancient sculptures, Michelangelo Buonarroti and Raphael, in whose art, according to Giorgio Vasari, history was fulfilled.

He also adopted motifs from his contemporaries Giuseppe Cesari, Annibale Carracci and Giovanni Girolamo Savoldo. Valeska von Rosen sees his imitatio as a subversive and ironic form of imitation, since it refers primarily to ambiguous aspects (e.g., potentially lascivious and homoerotic) of the works that were precisely not considered worthy of imitation in the eyes of his contemporaries; she sees it as a play on artistic norms that had become fragile.

In his paintings, Caravaggio linked modeling (di maniera) with depiction according to nature and model (alla prima). "His angels are painted 'after nature' as much as his earthly protagonists." Through the model arrangements he usually "staged,"

he brought both principles to bear. Among the most common misinterpretations is the view that Caravaggio painted his pictures without preparatory drawing. Recent research has demonstrated traces of underdrawing in works by Caravaggio.

Instead of the usual detailed preparatory drawings, he made brush sketches in lead white on the primed canvas and marked highlighted areas by incisioni with the brush handle. Findings of mercury salts in the primers of his paintings suggest that he used a pinhole camera to project his models onto the canvas prepared with light-sensitive salts and was thus able to preserve the image for half an hour, time enough to trace it.

Entombment of Christ, 1603/04, oil on canvas, 300 × 203 cm, Vatican Pinacoteca

Nor does the pictorial geometry (e.g., according to the golden section) suggest a purely prima-painterly technique, as has often been advocated in research since Roberto Longhi's Caravaggio studies.

Howard Hibbard pointed out that, conspicuously, while Caravaggio painted many semi-nudes and some sometimes risqué nudes of boys, youths, and men, he did not paint a single erotic female figure.

Caravaggio did not use to sign his works. However, on the painting of the Beheading of John the Baptist, his signature is found in the painted blood of the martyr; another exception: on an earlier version of Medusa (1596, private collection, Milan), he signed with the painted blood of the severed head "Michel A. f." (Michel Angelo fecit [= has made]).

Although many contemporary copies and derivative second and third versions with varying pictorial designs exist of his paintings, it remains unclear whether these were produced in Caravaggio's own workshop.

Caravaggio's models

The imagination of the Caravaggio legend has been fired not least by his models: androgynous youths and city-famous harlots. They are taken as evidence of Caravaggio's penchant for homosexuality and bisexuality.

The art historian Jutta Held takes up the accusation directed against him of being a painter of the "lowly of society" when she sees a "lowly social origin" reflected in the people he portrayed. Roberto Longhi,

Bacchus (c. 1596), Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

on the other hand, specifies that Caravaggio intended to paint neither the "lower of society" nor the "cream of society", but his own kind. "He took his figures from that stratum of ordinary people where gestures and feelings best preserved their originality, even in the most extreme circumstances".

A type favored by Caravaggio were light-skinned, "soft yet muscular boys" as portrayed in the paintings Bacchus (Uffizi Gallery, Florence), Youth bitten by a lizard (Fondazione Longhi, Florence and National Gallery, London), Victorious Cupid (Gemäldegalerie Berlin).

The Death of the Virgin Mary (1606)

Whether Caravaggio's servant or assistant Francesco Boneri, called "Cecco dal Caravaggio," who modeled for Victorious Cupid and John with the Ram (Capitoline Museums, Rome),

presumably also for The Sacrifice of Abraham (Uffizi, Florence), was also his "boy toy," as Baglioni's faithful pupil Tommaso Salini rumored in 1603 and a later hearsay statement by English traveler Richard Symonds suggested, remains speculation. Caravaggio's younger friend, Mario Minniti, also probably modeled for him.

His relationships with prostitutes are documented, namely with Lena and with Fillide Melandroni. Both have modeled for biblical female figures. Possibly for a later Galan, he also painted Fillide's own portrait (1601, Portrait of Fillide Melandroni; last in German possession, lost since 1945).

She is considered to have been the model for Magdalene in Martha Converts Magdalene, St. Catherine, and Judith in Judith and Holofernes, while Lena is thought to have been the model for the Pilgrim Madonna (also: Loreto Madonna), the Death of Mary, and the Madonna dei Palafrenieri.

The appearance of wickedness is greatly relativized with regard to both sets of relationships when one considers, first, that Caravaggio was penniless at the beginning of his career and could not pay models, and second, that respectable women were difficult to attract as models for his painting.

Portrait Fillide Melandroni (after 1601)

In some multi-figure paintings (Capture of Christ, Martyrdom of St. Matthew, Martyrdom of St. Ursula) Caravaggio added himself as a model, not as an active participant, but as an observer of the action. In the Roman version of David and Goliath, the severed head bears his features. However, there is no self-portrait of him that is designated as such.

Selected Works

From Caravaggio's twenty-year creative period from 1591 to 1610, sixty-seven works have survived as paintings by Caravaggio himself and another twenty-one attributed to him.

Fruit basket (1595/96). Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan

Early secular paintings of Caravaggio

The earliest of Caravaggio's surviving paintings is The Fruit-Peeling Boy (1591/92). Early subjects include youths and boys with fruit (Boy with Fruit Basket, 1593/94, Galleria Borghese Rome) or portrayed in dramatic moments (Youth Bitten by a Lizard, 1593/94, Longhi Collection, Florence) or posing as Bacchus (so-called Bacchino malato: 1593,

Galleria Borghese, Rome; Bacchus: c. 1596, Uffizi Gallery, Florence). His early paintings depict isolated persons, two- and multi-figure group representations were added over the years (The False Players, 1594/95; The Musicians, 1595).

Outstanding from this creative period are The Lute Player (1595/96, Hermitage (St. Petersburg) and 1596, Metropolitan Museum of Art), masterfully painted in two versions for the banker Vincenzo Giustiniani and the Cardinal Del Monte, in Caravaggio's words "the most beautiful picture he ever created," and Caravaggio's smallest painting,

The Fruit Basket (1595/96, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan). It is one of the earliest Italian still lifes. With the precision of scientific illustrations, he depicted fruits and leaves in the beginning process of decay, an allusion to the cycle of nature. It is his only surviving autonomous still life. In some paintings he combined still lifes with figures to create masterful compositions.

With the round painting of the Head of Medusa (1597, Uffizi Gallery, Florence), characterized as the "Poetics of the Scream", he created a mythological theme of "unparalleled representational expressiveness". Contemporary sources speak of the "serpentine head", of her "venomous mane, armed with a thousand serpents".

The discovery of the sacred

The first religious paintings depict the Penitent Magdalene (1594), Rest on the Flight into Egypt (1594), and Martha Converts Magdalene (1597/98).

The painting Judith and Holofernes (1598/99, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica Palazzo Barberini, Rome) was commissioned by Maffeo Barberini (later Pope Urban VIII), a neighbor during Caravaggio's stay at the palace of Monsignor Fantino Petrignani, who at the time was a chamber cleric responsible for papal finances.

Judith and Holofernes (1598/99)

In it Caravaggio depicts for the first time the scene of the beheading of the Assyrian army commander by the beautiful Jewish widow Judith. As a contrast, Caravaggio places next to the at once determined and disgusted actress the face of an old maid who stands ready to receive the head of Holofernes. The model for Judith was the harlot Fillide Melandroni, a model Caravaggio also preferred for other biblical female figures (Martha, Catherine).

Commissions for Roman churches

Six of his most famous paintings are in three Roman churches

The Contarelli Chapel (the funeral chapel of French Cardinal Mathieu Cointrel, called Contarelli in Italian) in the church of San Luigi dei Francesi was decorated with three works on St. Matthew the Apostle and Evangelist: the two side wings with St. Matthew's Calling to the Apostle and St. Matthew's Martyrdom, the altar with St. Matthew the Evangelist and the Angel (1599-1602).

A first version of the Evangelist with the Angel (1599, St. Matthew; last in German possession, lost since 1945) showed a barefoot peasant St. Matthew with crossed legs and a "pert boy" (Roberto Longhi) as the angel, which was rejected by the Congregation and ended up in the Giustinianis collection.

Matthew and the Angel (1602), Contarelli Chapel

Two paintings in the Cappella Cerasi of the church of Santa Maria del Popolo depict the Conversion of Paul (1601/1604) and the Crucifixion of Peter (1601/1604). They were commissioned by the papal treasurer general, Tiberio Cerasi, for his funeral chapel.

The Italian art critic Longhi called the works "perhaps the most revolutionary in the entire history of sacred art" because of their extreme naturalism, coupled with an unerring sense of abstract form. At the same time, Cerasi had commissioned Annibale Carracci of Bologna to depict the Assumption of Mary (c. 1600) for the chapel's altar.

Unlike Carracci's work, which the painter delivered on time and met with the client's approval, Cerasi rejected Caravaggio's work for the side walls, forcing him to create a new version, which was completed only after Cerasi's death (1601) and installed in 1605. The first rejected version is now in the Odescalchi collection.

The Crucifixion of St. Peter the Apostle (1601/1604), Cerasi Chapel

There is a brutal contrast between Carracci's and Caravaggio's paintings, not only in content but also in style. Mary's Assumption is painted in sumptuous bright and glittering colors (including ultramarine) and is close to the idealized splendor and beauty of the High Renaissance.

In contrast, Caravaggio painted the side pictures with the converted Paul and crucified Peter in aggressive directness in his typical gloomy tenebrism, with few and cheap colors, an earthy, ocher and lead white coloring. In the painting of the crucified Peter, against a black background, Peter, crucified upside down at his request (out of humility before the crucified Christ), juts into the foreground of the painting.

He resembles a rustic old man and lies, dramatically illuminated, sloping diagonally on a crude cross. Together with the toiling three executioner's slaves (two only in back view), who perform their work "dispassionately," "like dull beasts of burden," the four people form a cross.

The church of Sant'Agostino houses the Pilgrim Madonna or Loreto Madonna (after the pilgrimage site of Loreto) of 1604/05 in the Cappella Cavalletti as another of Caravaggio's paintings.

The Pilgrim Madonna (1604/05), Cavalletti Chapel

Although the chapel's altarpiece shows Mary in the classical pose of an ancient statue, standing with the child in her arms, it is set against a plain brick wall, as if she had just met the pilgrims at the threshold of their home.

In a characteristic contrast of light and dark, the light falls on her face and on the child from the upper left. In front of her kneel two poorly dressed pilgrims, barefoot like Mary. The picture is subject to a strictly composed golden section.

He created another altarpiece, The Entombment of Christ (1603/04, now in the Vatican Pinacoteca), for a funeral chapel in the church of the Oratorians, Santa Maria in Vallicella.

In creating the body, Caravaggio used the marble statue of the Pietà (1499, St. Peter's Basilica) by his namesake, Michelangelo Buonarroti, as a model. Immediately upon public accessibility, it was considered by Caravaggio's early biographers to be one of his most accomplished works.

The painting was also disseminated as an engraving and copied many times, not only in the 17th century, by Rubens, among others, and later by Fragonard, Géricault, and Cézanne.

As mentioned above, the paintings Caravaggio did on ecclesiastical commissions were often controversial: Five of his Roman altarpieces were rejected by the relevant congregations or priesthoods "with reference to the defective decorum."

Nevertheless, ecclesiastical dignitaries valued his depictions of biblical themes and incorporated them into their private collections.

The painting Death of Mary (1605/06, now in the Louvre, Paris) ordered by the benefactor Laerzio Cherubini for the church of the Reform Order of the Discalced Carmelites (Santa Maria della Scala) was removed from the altar by the Carmelites after a short time because of the rumor that the model of Mary depicted was a harlot. On the recommendation of Peter Paul Rubens, it was subsequently purchased by the Duke of Mantua.

Other Roman commissions

Probably for the banker Ottavio Costa, he painted Martha Converted Magdalene (1597/98, Detroit Institute of Arts). The painting shows the two women as half-figures. It depicts the moment of the sinner Magdalene's conversion, but which Martha does not yet seem to have grasped.

Magdalena points to the (divine) light bundling in the mirror, which at the same time illuminates her face. Caravaggio was the first to depict the moment of Magdalene's conversion in painting.

One of Caravaggio's most famous paintings is Cupid as Victor (1601/02, Gemäldegalerie Berlin). It shows a winged boy in provocative nudity, "rendered as perfectly as an ancient statue." Smilingly displaying his sex and crotch, he strides over props of music (lute, violin, music book), symbols of power and glory (armor, crown ring, laurel branch), and paraphernalia of erudition (protractor, book, quill pen).

Cupid as victor (1601/02), Gemäldegalerie Berlin

Caravaggio's competitor Giovanni Baglione painted a counterpart, Amor sacro e amor profano "Heavenly and Earthly Cupid" (1602, Gemäldegalerie Berlin), in which the heavenly Cupid chastises the earthly one. For this painting, however, Baglione earned scorn and ridicule.

The dispute led to a libel suit brought by Baglione in 1603 against Caravaggio, two other painters (Orazio Gentileschi, Fillipo Trisengni), and the architect Onorio Longhi.

Two autograph versions of Infidel Thomas also have an iconic status. He painted an ecclesiastical "Trieste" version for Girolamo Mattei around 1601,

which is now in a private collection, and a secular "Potsdam" version, probably commissioned by the wealthy and educated collector Marchese Vincenzo Giustiniani and then later entered the Prussian royal collection and survived the Second World War unscathed and can now be admired in the Palais in Sanssouci, Potsdam.

Immediately after their completion, the two paintings "triggered numerous copies and derivations". They show in a demonstrative gesture, how the doubting apostle Thomas, puts his finger into the side wound of Christ, whereby this still leads him his hand.

The unbeliever is depicted like a peasant, dressed in a robe torn at the shoulder and with dirt under his fingernails. The composition of the picture is such that the viewer is directly involved in the event and feels the pain of penetration.

The Madonna of the Rosary (1605/06), Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, a large altarpiece (364.5 × 249.5 cm) with Dominican iconography, is the only painting of a donor in Caravaggio's oeuvre. Who commissioned the painting is unclear; the donor portrayed on the left edge of the painting could not be identified.

St. Jerome (1606), Galleria Borghese, Rome

Probably his last Roman work is Saint Jerome (1606, Galleria Borghese, Rome), which he painted for Cardinal Scipione Borghese. It shows the Church Father, wrapped in a cardinal red cloak and concentrated at his work, the translation of the Bible from Hebrew or Greek into Latin. "In perfect symmetry, whose central axis is the binding of the opened text, the skull and the head of the saint are set in balance. Still life and figure, red and white are linked by an overlong arm that dips the pen as if alienated. At the center of the pictorial structure is the text, the Vulgate, for the Counter-Reformation Church the only valid biblical text."

Caravaggio's Works from the years of exile

The years of exile that Caravaggio spent in Naples, Malta, Sicily, and again in Naples were productive years. Among the first works of this period are the altarpiece Seven Works of Mercy (1606/07, Church of Pio Monte della Misericordia, Naples), a second version of The Last Supper at Emmaus (1606, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan), and the second execution of the famous painting David and Goliath (1606/07, Galleria Borghese, Rome).

David with the head of Goliath, c. 1600/01, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

The altarpiece features an "extremely rich compositional structure" that, according to Giorgio Bonsati, "makes the planar division of this painting probably the most varied in Caravaggio's entire oeuvre."

The first version of David and Goliath hangs in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Like this one, the second version shows a boyish David holding Goliath's severed head with his horizontally outstretched left hand. The different physiognomies of Goliath are striking. In the Roman painting, Caravaggio has provided the severed head with a self-portrait, in which Ebert-Schifferer sees a "shocking self-abasement."

Caravaggio, it is assumed, wanted to persuade Cardinal Scipione Borghese with his depiction as a "dying defeated man" to plead with his uncle, Pope Paul V, to pardon him. Various art historians consider it Caravaggio's last work.

David with the head of Goliath (Roman version), 1606/07, Galleria Borghese, Rome

Thanks to his protectors, Caravaggio was able to take the works to Rome in a carriage belonging to the Colonna family, of which the Emmaus Supper was given to his patron, the banker Ottavio Costa, and the David and Goliath to the gifted Scipione Borghese.

Of note from this period are two different versions of the Flagellation of Christ (one circa 1606/07 in the Musée des beaux-arts de Rouen, the other in 1607 in the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples; illustrated above) and three altarpieces left at the stations of his flight:

- Salome with the head of St. John the Baptist, ca. 1607, National Gallery (London)

The Seven Works of Mercy (1606, Pio Monte della Misericordia, Naples), The Beheading of John the Baptist (1608, St. John's Co-Cathedral, Valletta), The Burial of St. Lucia (1608, Santa Lucia al Sepolcro, Syracuse), and Salome with the Head of St. John the Baptist (1607, National Gallery (London)).

The monumental painting The Beheading of John the Baptist (pictured above) is the largest picture (361 × 520 cm) Caravaggio ever painted. In the painting, which is strictly composed geometrically, all the figures are on the left half, with the exception of two prisoners who witness the action on the right half behind a lattice window.

Salome with the head of John the Baptist, 1609 (Escorial, Madrid)

The painting captures the moment of the severing of John's head with sword and dagger, a work that the executioner performs dispassionately on the man lying on a sheepskin, just as a butcher slaughters an animal. Beside him stands a maid, ready to serve, with her eyes fixed on the golden bowl in her hands that is to hold the martyr's head for Salome.

Another couple is the head of the prison and an old woman. The head of the prison with bulky keys on his belt points emotionlessly to the bowl. The old woman next to him is the only person who shows emotion. Encompassing her head with her hands, she gazes at the gruesome process.

She stands for Christian mercy. Roberto Longhi considers the "scene of grandiose tragedy" to be "more merciless than anything Caravaggio has created before."

Caravaggio, who usually did not sign his paintings, provided this one with a spectacular signature: In the (painted) blood of the martyr he wrote fMichelAn [meaning Frater (brother) Michelangelo]. With this he inscribed himself into the community of the Brothers of the Order of Malta. The painting was, so to speak, his entry obolus.

His painting Salome with the Head of St. John the Baptist (1609, Escorial Madrid) is a variant of the London painting Salome with the Head of St. John the Baptist (1607, National Gallery, London),

which was discovered only in 1959 by Roberto Longhi and seemed to him to be "the culmination of all Caravaggio's work." Both versions differ greatly. "In the late version, the representation seems to emerge from a boundless darkness". Salome stares the viewer in the eye, while the Executioner gazes musingly at his work.

Other paintings of Caravaggio

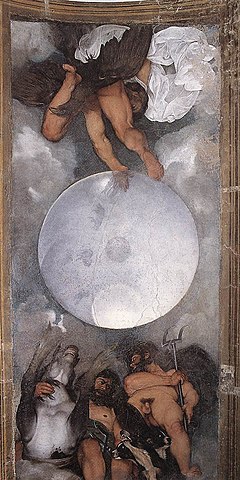

Jupiter, Neptune and Pluto (1599), the only known ceiling painting

Vocation of St. Matthew (1600)

Last Supper at Emmaus (1601)

The Entombment of Christ (ca. 1603/04)

Doubting Thomas (ca. 1601/02)

Aftermath and reception

Giorgio Bonsanti attests to Caravaggio's painting a "pioneering power of renewal" comparable to that of Giotto, Masaccio, and Paul Cezanne; it "continued to have an effect throughout Western painting and determined its course."

Caravaggism in the early Baroque

Caravaggio worked largely alone and had no direct pupils. Nevertheless, his work had a lasting influence on early Baroque painting: according to the British art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon, hardly any painter of note could escape his influence in the years after his death.

Caravaggio's first imitator was Bartolomeo Manfredi, who also contributed to the international spread of Caravaggism. Artists who still knew Caravaggio personally and are counted among Caravaggesque painting also include Orazio Gentileschi, Carlo Saraceni, Giovanni Baglione, Orazio Borgianni, and Mario Minniti; artists who no longer knew their early deceased model were Bartolomeo Cavarozzi, Leonello Spada, Giovanni Serodine, and Artemisia Gentileschi.

Bartolomeo Manfredi: Capture of Christ, ca. 1613-1618, oil on canvas, 120 × 174 cm, National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo.

The most striking features of the style known as Caravaggism were the relative close-up view of the persons depicted, the "realism" in the unadorned ordinariness of the scenes depicted with the choice of the "dramatic moment just before or just after the climax," and its design devices of chiaroscuro painting with effective lighting effects and foreshortening of proportions in the composition.

Both contradicted the Renaissance maniera and mannerism, but also the idealizing classicism of the Carracci school. It must be emphasized that the painters assigned to Caravaggism were by no means all mere imitators of mediocre quality, but that among them were great artists who processed his influences in a very personal and original way, often mixed with other (for example, Venetian) tendencies, and who succeeded in developing a style all their own (for example, Orazio Gentileschi).

Battistello Caracciolo: Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane, 1615-1617, oil on canvas, 148 × 124 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Some painters followed the example only temporarily (also Gentileschi or Simon Vouet), and even Guido Reni, who was considered the epitome of classicism, used caravaggesque means at times and depending on the content of the picture (or the client ?).

Peter Paul Rubens studied Caravaggio's Entombment of Christ closely during his stay in Rome (1603/04, Vatican Picture Gallery, Vatican) and made a free variation of it (1614, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa), but, as is well known, followed completely different ideals in his further career.

Caravaggio had a particularly lasting influence on Neapolitan painting, and Battistello Caracciolo is considered his first successor there. Jusepe de Ribera, who also worked in Naples, was one of the most important, independent and influential Caravaggio successors, especially since he also influenced Spanish painting (including Francisco de Zurbarán and the early Diego Velázquez).

Caravaggesque tenebrism in Naples was increasingly mixed with other influences from the 1620s onward, which also brought more elegance back into the representations. Roberto Longhi still sees Caravaggesque influences in the work of the Calabrese Mattia Preti, who was also active in Naples.

Since Rome was considered the definitive center of painting at the time, young painters flocked there from all the countries of Europe, who, especially up to the 1620s, processed influences from Caravaggio's works in their own way, including the French Claude Vignon, Simon Vouet, Nicolas Régnier, Nicolas Tournier, Valentin de Boulogne, Louis Finson, and Trophime Bigot. Many painters also traditionally came to Rome from the Netherlands, including Hendrick Terbrugghen, Gerard van Honthorst, and Dirck van Baburen, who studied Caravaggio's work and were later called the Utrecht Caravaggists. All these artists, although they did not meet Caravaggio personally, reached Rome when his style was imitated by his direct successors, and also had the opportunity to see Caravaggio's paintings in churches. A drawn copy of Honthorst's Crucifixion of Peter in Santa Maria del Popolo has survived. Moreover, during his stay in Rome, Honthorst stayed at the home of one of his patrons, the banker Vincenzo Giustiniani, who reportedly owned no fewer than fifteen Caravaggios in his collection. Rembrandt, who never visited Italy, became acquainted with Caravaggio's painting style through the Utrecht Caravaggists. He can "also be considered a representative of Caravaggism, albeit a rather late one. His turn to a radical realism, to which he adhered until his end, is hardly conceivable without the example of Caravaggio and his successors. This is also true of Rembrandt's use of light."

Painters influenced by Caravaggio also include: Matthias Stom, Georges de la Tour and Johann Ulrich Loth. Caravaggio influences can also be found in paintings by Jan Vermeer. Still life and genre painting of the early Italian, French and Dutch Baroque periods was also described as Caravaggesque.

Even in later art periods, Andrew Graham-Dixon discovered a Caravaggio design influence namely in Jacques Louis David's Death of Marat and Théodore Géricault's Raft of the Medusa.

While painting elsewhere in Italy and abroad continued for decades under a clear Caravaggesque influence, in Rome itself the naturalistic-tenebrist Caravaggio fashion had never been the only important artistic trend in the first decades of the 17th century:

The painters of the Carracci school were just as successful and to some extent also dealt with the Caravaggesque fashion (especially Reni, Lanfranco, Guercino). After 1620, their "classicist" Baroque was finally able to assert itself in Rome and then soon passed into the High Baroque (with Pietro da Cortona).

Subsequent generations of artists could not do much with Caravaggio's relentless, gloomy naturalism, which had little interest in beauty; Nicolas Poussin, in particular, saw in him "an anarchic furor that had come into the world to destroy painting." Bellori, in his Vite (1672),

admitted that Caravaggio's naturalism, after the artificiality of Mannerism, "was in part salutary," but also "very harmful, and it turned every ornament and good custom of painting upside down."

Rediscovery and modern myths in the 20th and 21st centuries

Already a hundred years after his death, Caravaggio was almost forgotten. He experienced his rediscovery in the 20th century. The Italian art historian Roberto Longhi, who curated the large exhibition "Mostra del Caravaggio e dei Caraveggeschi" in Milan in 1951,

in addition to a highly acclaimed monograph, contributed significantly to this. In the following decades until today, the number of publications about the artist on an international level has increased so much that one can speak of a certain confusion.

In addition to the art historical study of Caravaggio, his eventful life has also inspired writers, directors and choreographers, who have dramatically highlighted in a series of novels and films mainly those events from which a "black legend" can be woven as a "wicked artist".

Among the films, Derek Jarman's multi-award-winning 1986 Caravaggio is a sophisticated construct of art, sex, and violence, with an explosive love triangle, with no claim to historical truth, in which a kind of myth is propagated of the violent, bisexual, and promiscuous painter-genius who violated all social conventions.

Jarman interpreted Caravaggio "as an outsider to society [...] in whom he could recognize himself," as an outlaw "who would not allow himself to be restricted in either his artistic or sexual freedoms by any laws or conventions."

The Düsseldorf museum director Jean-Hubert Martin reacted to the "black legend" by inviting eight renowned writers (among them Henning Mankell and Ingrid Noll) on the occasion of the 2006 exhibition to be inspired by the "rebellious character" of Caravaggio and his work with fictional short stories and to "bring the artist himself to life. The resulting anthology is tellingly titled Painter, Murderer, Myth.

The ballet Caravaggio by the German choreographer Jochen Ulrich also takes up the characteristic events in the life and work of the painter, implemented in dance with always the same, dynamic and contrasting movement patterns and in the illumination of the light-dark colors significant for the painter.

Miscellaneous

In 2012, after two years of research on the estate of the painter Simone Peterzano kept in the Castello Sforzesco in Milan, two Italian experts claimed to have discovered about a hundred of Caravaggio's bequeathed early works; he is said to have produced them from 1584 to 1588, when he took lessons with Peterzano.

Caravaggio and his paintings Buona ventura and Fruit Basket on the Italian 100,000 lira banknote, issued 1983-2001

The most renowned Italian Caravaggio expert Maurizio Calvesi cast doubt on this claim, as did Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, a renowned Caravaggio biographer. Other experts also doubt it.

In April 2014, another Judith and Holofernes (1610) oil painting was found in southern France near Toulouse. While some art experts such as Eric Turquin attribute it to Caravaggio and expect a sale value of already 100 million euros, others are skeptical and, like the French Minister of Culture, among others, demand a detailed examination of the painting.

Caravaggio and his paintings Buona ventura and Fruit Basket were depicted on the last Italian 100,000 lira banknote issued by the Banca d'Italia between 1983 and 2001.